exoplanet

exoplanet

exoplanet

exoplanet

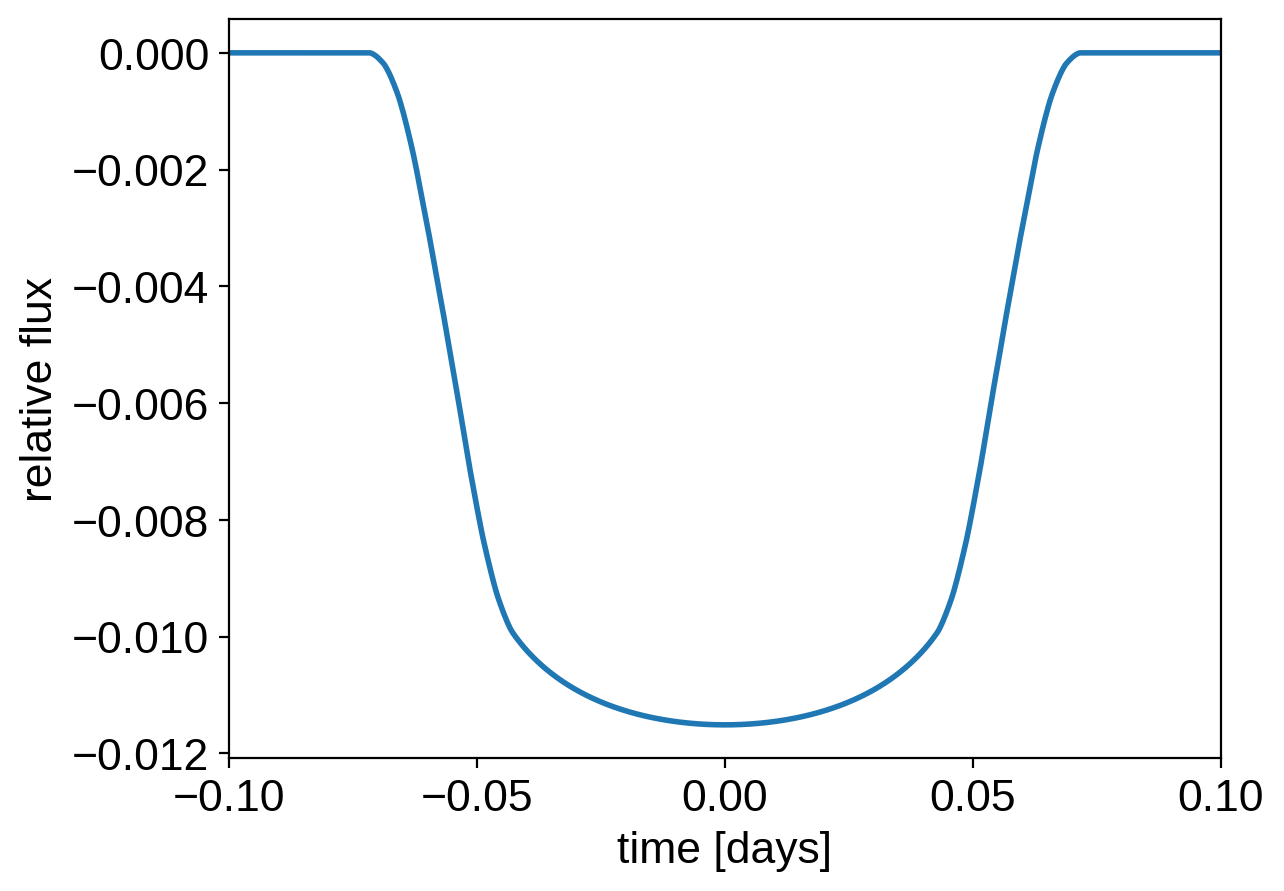

exoplanet includes methods for computing the light curves transiting planets. In its simplest form this can be used to evaluate a light curve like you would do with batman, for example:

[3]:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import exoplanet as xo

# The light curve calculation requires an orbit

orbit = xo.orbits.KeplerianOrbit(period=3.456)

# Compute a limb-darkened light curve using starry

t = np.linspace(-0.1, 0.1, 1000)

u = [0.3, 0.2]

light_curve = (

xo.LimbDarkLightCurve(u)

.get_light_curve(orbit=orbit, r=0.1, t=t, texp=0.02)

.eval()

)

# Note: the `eval` is needed because this is using Theano in

# the background

plt.plot(t, light_curve, color="C0", lw=2)

plt.ylabel("relative flux")

plt.xlabel("time [days]")

_ = plt.xlim(t.min(), t.max())

But the real power comes from the fact that this is defined as a Theano operation so it can be combined with PyMC3 to do transit inference using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo.

In this section, we will construct a simple transit fit model using PyMC3 and then we will fit a two planet model to simulated data. To start, let’s randomly sample some periods and phases and then define the time sampling:

[4]:

np.random.seed(123)

periods = np.random.uniform(5, 20, 2)

t0s = periods * np.random.rand(2)

t = np.arange(0, 80, 0.02)

yerr = 5e-4

Then, define the parameters. In this simple model, we’ll just fit for the limb darkening parameters of the star, and the period, phase, impact parameter, and radius ratio of the planets (note: this is already 10 parameters and running MCMC to convergence using emcee would probably take at least an hour). For the limb darkening, we’ll use a quadratic law as parameterized by Kipping (2013). This reparameterizations is

implemented in exoplanet as custom PyMC3 distribution exoplanet.distributions.QuadLimbDark.

[5]:

import pymc3 as pm

with pm.Model() as model:

# The baseline flux

mean = pm.Normal("mean", mu=0.0, sd=1.0)

# The time of a reference transit for each planet

t0 = pm.Normal("t0", mu=t0s, sd=1.0, shape=2)

# The log period; also tracking the period itself

logP = pm.Normal("logP", mu=np.log(periods), sd=0.1, shape=2)

period = pm.Deterministic("period", pm.math.exp(logP))

# The Kipping (2013) parameterization for quadratic limb darkening paramters

u = xo.distributions.QuadLimbDark("u", testval=np.array([0.3, 0.2]))

r = pm.Uniform(

"r", lower=0.01, upper=0.1, shape=2, testval=np.array([0.04, 0.06])

)

b = xo.distributions.ImpactParameter(

"b", ror=r, shape=2, testval=np.random.rand(2)

)

# Set up a Keplerian orbit for the planets

orbit = xo.orbits.KeplerianOrbit(period=period, t0=t0, b=b)

# Compute the model light curve using starry

light_curves = xo.LimbDarkLightCurve(u).get_light_curve(

orbit=orbit, r=r, t=t

)

light_curve = pm.math.sum(light_curves, axis=-1) + mean

# Here we track the value of the model light curve for plotting

# purposes

pm.Deterministic("light_curves", light_curves)

# ******************************************************************* #

# On the folowing lines, we simulate the dataset that we will fit #

# #

# NOTE: if you are fitting real data, you shouldn't include this line #

# because you already have data! #

# ******************************************************************* #

y = xo.eval_in_model(light_curve)

y += yerr * np.random.randn(len(y))

# ******************************************************************* #

# End of fake data creation; you want to include the following lines #

# ******************************************************************* #

# The likelihood function assuming known Gaussian uncertainty

pm.Normal("obs", mu=light_curve, sd=yerr, observed=y)

# Fit for the maximum a posteriori parameters given the simuated

# dataset

map_soln = xo.optimize(start=model.test_point)

optimizing logp for variables: [b, r, u, logP, t0, mean]

109it [00:05, 21.71it/s, logp=2.479354e+04]

message: Desired error not necessarily achieved due to precision loss.

logp: 24787.977771807487 -> 24793.53942561123

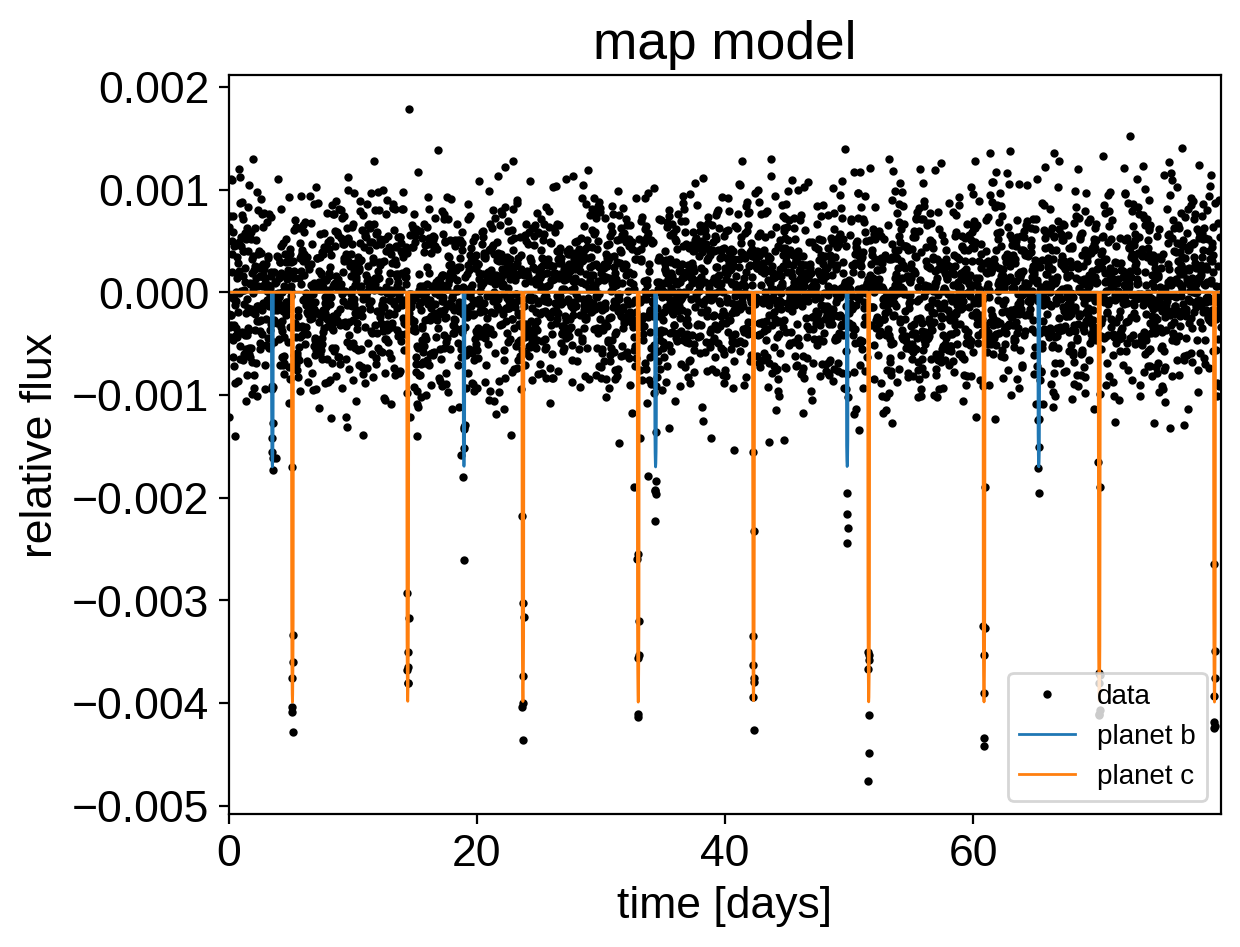

Now we can plot the simulated data and the maximum a posteriori model to make sure that our initialization looks ok.

[6]:

plt.plot(t, y, ".k", ms=4, label="data")

for i, l in enumerate("bc"):

plt.plot(

t, map_soln["light_curves"][:, i], lw=1, label="planet {0}".format(l)

)

plt.xlim(t.min(), t.max())

plt.ylabel("relative flux")

plt.xlabel("time [days]")

plt.legend(fontsize=10)

_ = plt.title("map model")

Now, let’s sample from the posterior defined by this model. As usual, there are strong covariances between some of the parameters so we’ll use init="adapt_full".

[7]:

np.random.seed(42)

with model:

trace = pm.sample(

tune=3000,

draws=3000,

start=map_soln,

cores=2,

chains=2,

init="adapt_full",

target_accept=0.9,

)

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using adapt_full...

Multiprocess sampling (2 chains in 2 jobs)

NUTS: [b, r, u, logP, t0, mean]

Sampling 2 chains for 3_000 tune and 3_000 draw iterations (6_000 + 6_000 draws total) took 86 seconds.

After sampling, it’s important that we assess convergence. We can do that using the pymc3.summary function:

[8]:

pm.summary(trace, varnames=["period", "t0", "r", "b", "u", "mean"])

[8]:

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_mean | ess_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| period[0] | 15.448 | 0.002 | 15.443 | 15.452 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2031.0 | 2031.0 | 2252.0 | 2769.0 | 1.0 |

| period[1] | 9.292 | 0.000 | 9.292 | 9.293 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4333.0 | 4333.0 | 4340.0 | 4274.0 | 1.0 |

| t0[0] | 3.503 | 0.006 | 3.493 | 3.514 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2013.0 | 2012.0 | 2177.0 | 3727.0 | 1.0 |

| t0[1] | 5.121 | 0.001 | 5.119 | 5.124 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4889.0 | 4889.0 | 4894.0 | 4212.0 | 1.0 |

| r[0] | 0.040 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2385.0 | 2385.0 | 2409.0 | 3729.0 | 1.0 |

| r[1] | 0.059 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2438.0 | 2438.0 | 2514.0 | 3467.0 | 1.0 |

| b[0] | 0.670 | 0.048 | 0.576 | 0.742 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1539.0 | 1539.0 | 1792.0 | 2775.0 | 1.0 |

| b[1] | 0.404 | 0.038 | 0.331 | 0.468 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 2345.0 | 2345.0 | 2494.0 | 3045.0 | 1.0 |

| u[0] | 0.377 | 0.207 | 0.012 | 0.724 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 4520.0 | 4361.0 | 4324.0 | 3392.0 | 1.0 |

| u[1] | 0.268 | 0.340 | -0.339 | 0.822 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 2318.0 | 2318.0 | 2197.0 | 2924.0 | 1.0 |

| mean | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 6190.0 | 3936.0 | 6192.0 | 4197.0 | 1.0 |

That looks pretty good! Fitting this without exoplanet would have taken a lot more patience.

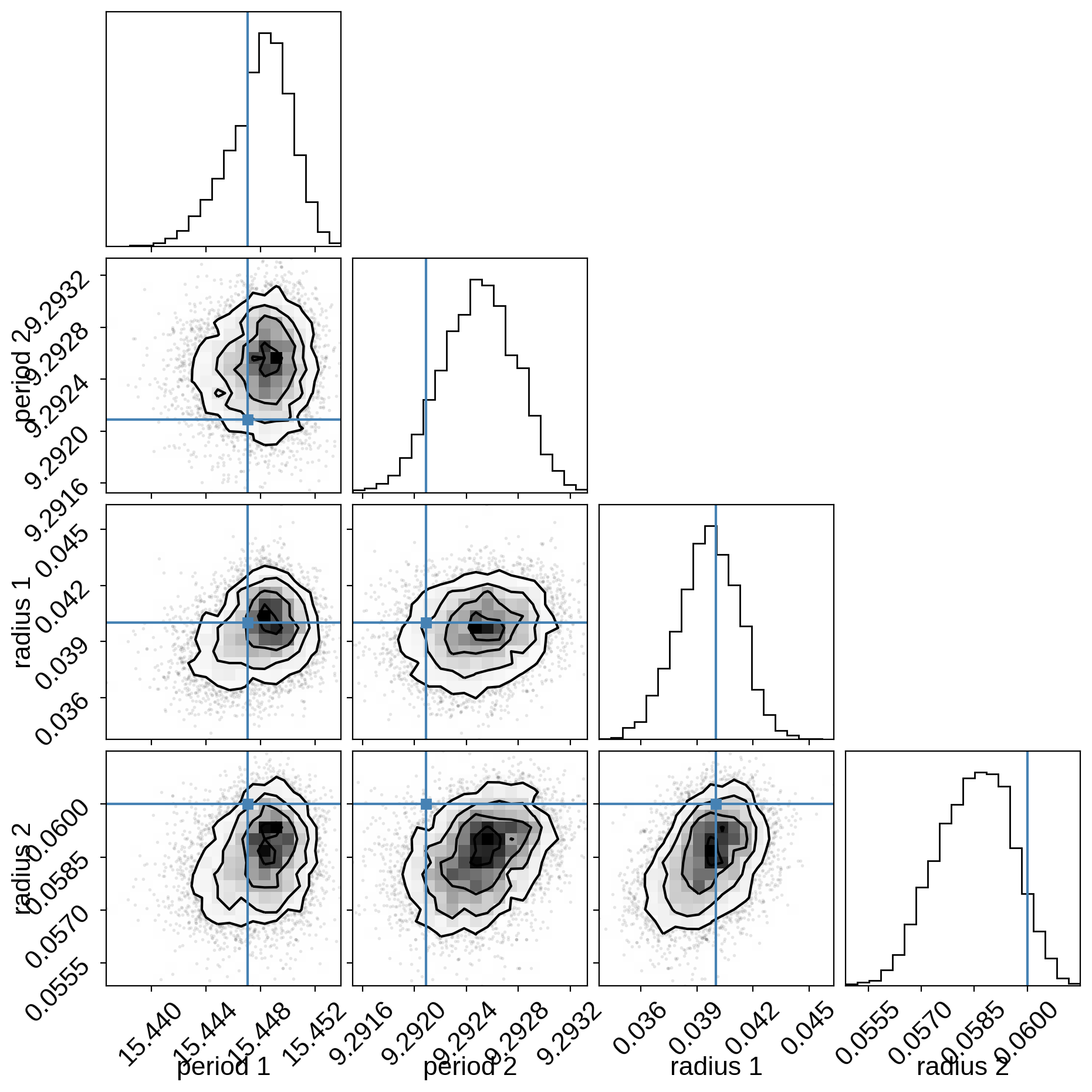

Now we can also look at the corner plot of some of that parameters of interest:

[9]:

import corner

samples = pm.trace_to_dataframe(trace, varnames=["period", "r"])

truth = np.concatenate(

xo.eval_in_model([period, r], model.test_point, model=model)

)

_ = corner.corner(

samples,

truths=truth,

labels=["period 1", "period 2", "radius 1", "radius 2"],

)

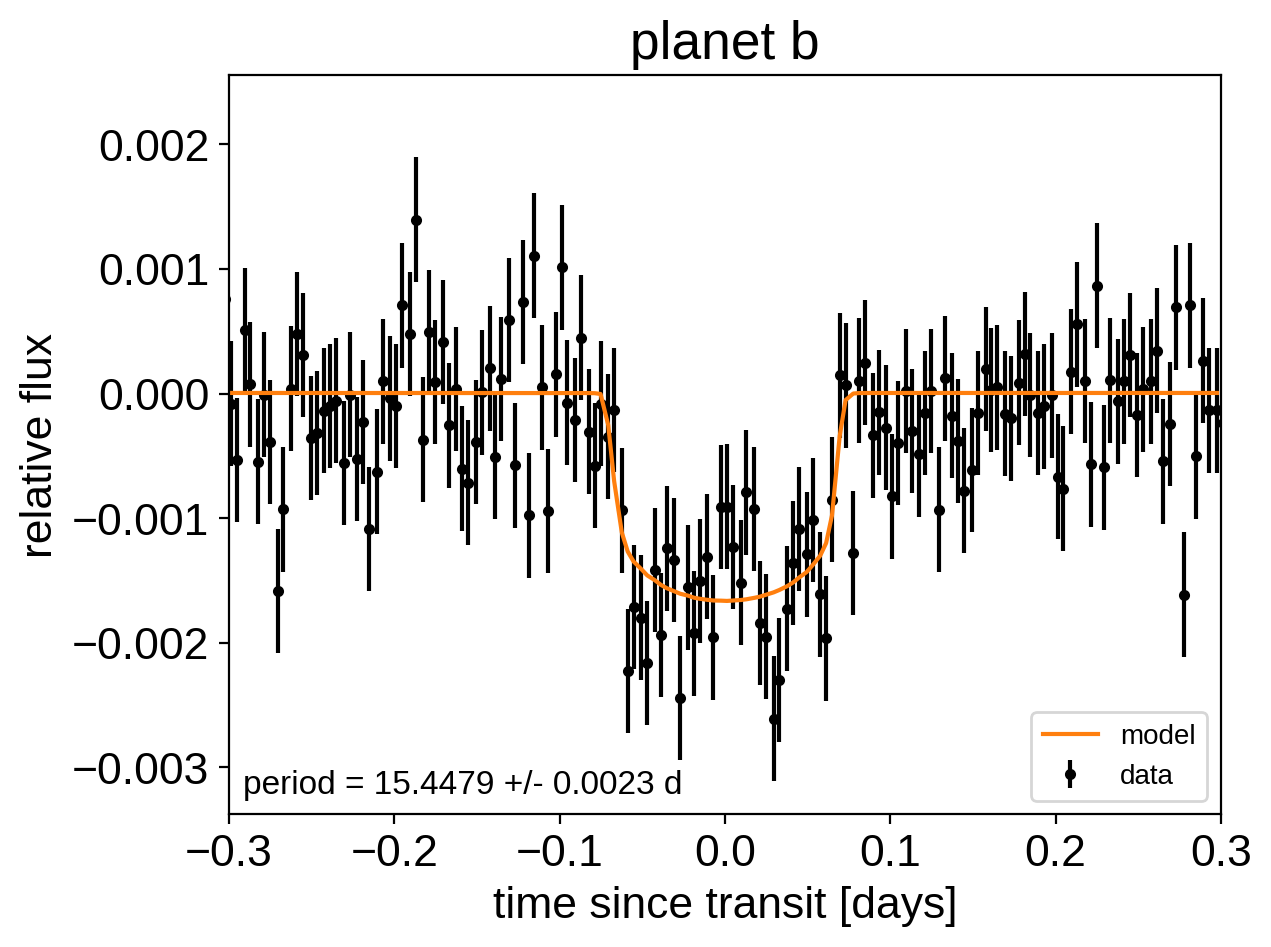

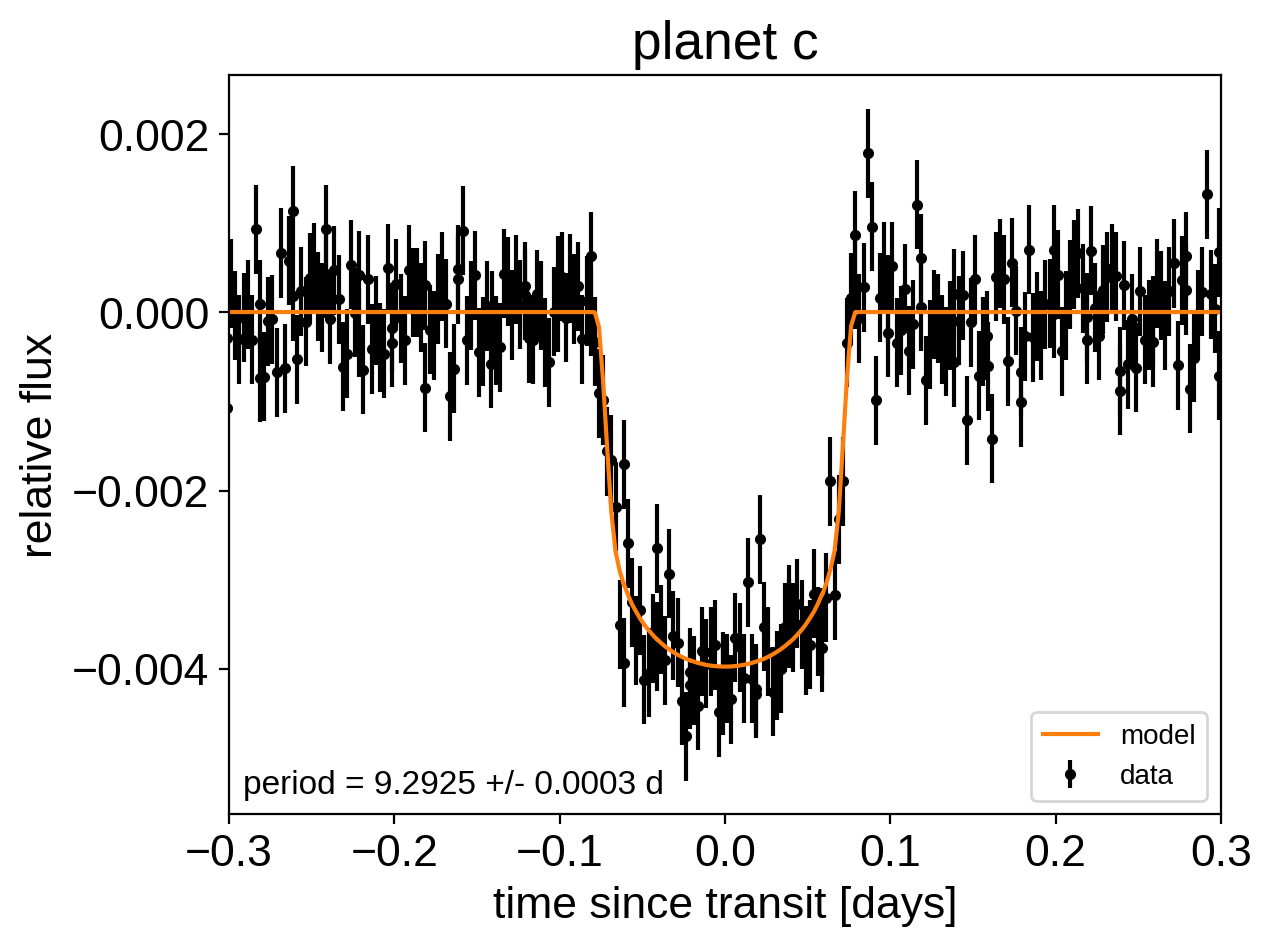

Like in the Radial velocity fitting tutorial, we can make plots of the model predictions for each planet.

[10]:

for n, letter in enumerate("bc"):

plt.figure()

# Get the posterior median orbital parameters

p = np.median(trace["period"][:, n])

t0 = np.median(trace["t0"][:, n])

# Compute the median of posterior estimate of the contribution from

# the other planet. Then we can remove this from the data to plot

# just the planet we care about.

other = np.median(trace["light_curves"][:, :, (n + 1) % 2], axis=0)

# Plot the folded data

x_fold = (t - t0 + 0.5 * p) % p - 0.5 * p

plt.errorbar(

x_fold, y - other, yerr=yerr, fmt=".k", label="data", zorder=-1000

)

# Plot the folded model

inds = np.argsort(x_fold)

inds = inds[np.abs(x_fold)[inds] < 0.3]

pred = trace["light_curves"][:, inds, n] + trace["mean"][:, None]

pred = np.median(pred, axis=0)

plt.plot(x_fold[inds], pred, color="C1", label="model")

# Annotate the plot with the planet's period

txt = "period = {0:.4f} +/- {1:.4f} d".format(

np.mean(trace["period"][:, n]), np.std(trace["period"][:, n])

)

plt.annotate(

txt,

(0, 0),

xycoords="axes fraction",

xytext=(5, 5),

textcoords="offset points",

ha="left",

va="bottom",

fontsize=12,

)

plt.legend(fontsize=10, loc=4)

plt.xlim(-0.5 * p, 0.5 * p)

plt.xlabel("time since transit [days]")

plt.ylabel("relative flux")

plt.title("planet {0}".format(letter))

plt.xlim(-0.3, 0.3)

As described in the Citing exoplanet & its dependencies tutorial, we can use exoplanet.citations.get_citations_for_model() to construct an acknowledgement and BibTeX listing that includes the relevant citations for this model. This is especially important here because we have used quite a few model components that should be cited.

[11]:

with model:

txt, bib = xo.citations.get_citations_for_model()

print(txt)

This research made use of \textsf{exoplanet} \citep{exoplanet} and its

dependencies \citep{exoplanet:agol20, exoplanet:arviz, exoplanet:astropy13,

exoplanet:astropy18, exoplanet:exoplanet, exoplanet:kipping13,

exoplanet:luger18, exoplanet:pymc3, exoplanet:theano}.

[12]:

print("\n".join(bib.splitlines()[:10]) + "\n...")

@misc{exoplanet:exoplanet,

author = {Daniel Foreman-Mackey and Arjun Savel and Rodrigo Luger and

Ian Czekala and Eric Agol and Adrian Price-Whelan and

Emily Gilbert and Timothy D. Brandt and Tom Barclay and Luke Bouma},

title = {exoplanet-dev/exoplanet v0.4.4},

month = jan,

year = 2021,

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.1998447},

url = {https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1998447}

...